Chaitra Yadavar*

I personally remember sweating an unlimited amount even at 10 am as I stepped out to catch a local train to attend a meeting or to buy something from a grocery shop in May 2016. I didn’t remember it being this hot in the last 3 years. In the local trains, women would be discussing how they wake up in the morning to get ready for office, they would be completely covered in sweat. I used to thank my stars when I heard this as my family used to put the AC on before sleeping. All my friends and me, whoever used to work from home, switched rooms whichever were facing East and started working whichever room was facing West, in the mornings. It was unbearably hot!

I wasn’t surprised when I read that the European Geosciences Union published a study in April 2016 that examined the impact of a 1.5 degree Celsius vs. a 2.0 C temperature increase by the end of the century.

Heat waves would last around a third longer or rain storms would be about a third more intense. Also, the increase in sea level would be approximately a third higher and the percentage of tropical coral reefs at risk of severe degradation would be roughly that much greater.

In 2015, we saw global average temperatures a little over 1℃ above pre-industrial levels (before the industrial era began), and 2016 is proving to be even hotter. In February and March of this year, temperatures were already 1.38℃ above pre-industrial averages.

There are major reasons to be concerned about these factors being in India. South Asia’s vulnerability to these and future disasters is great, principally for reasons of population and poverty. The majority of South Asian countries are low or lower-middle income countries that already struggle to support the daily needs of their growing populations. Because poorer households dedicate more of their budgets to food, they are the most sensitive to weather-related shocks on agriculture that can make daily staple food unaffordable.

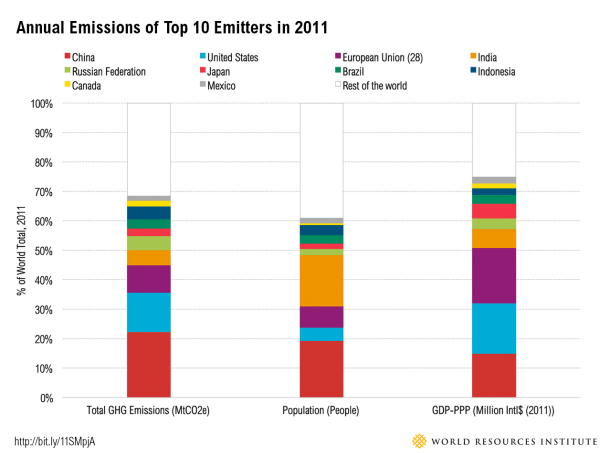

The point to remember in this scenario is that majority of the Greenhouse Gas emissions are let out by the first-world countries and the third-world and comparatively poorer countries like India have to suffer its disastrous consequences.

The destruction from flooding could wreak havoc in South Asia’s low-lying and urban areas. Extreme heat is already disrupting the growing season for regions in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Wheat production in the Indian portion of the Indo-Gangetic Plains, a fertile area that also encompasses parts of Pakistan and Bangladesh, may decrease by up to 50 per cent by 2100, harming the hundreds of millions of people who rely on it for sustenance.

The story of 1.5 C

Around 180 countries have so far signed the Paris climate agreement in which they pledged not only to limit the global temperature rise since pre-industrial times to “well below” 2C but to do their very best to keep them to 1.5C.

But as recorded temperatures this year have edged above 1C, scientists believe we are already dangerously close with the 1.5 degree target.

This new study suggests that it will “almost certainly be surpassed”, at least over land, based on the amount of CO2 already in the atmosphere.

Other researchers agree that keeping temperatures at the 1.5 figure is going to be a significant, if not impossible, challenge. But if the world is to take the 1.5 target seriously, then a serious discussion needs to be held about the implications of that goal.

After all, this is a global climate agreement. And to many countries, passing those temperature limits could be a disaster.

A ticking heat time-bomb: India

In the past few years in India, at times there is a severity in temperatures, at times it rains in odd months. The unpredictability and large scale loss which climate change has brought about is visible in states like Rajasthan. On May 19 2016, India’s all-time temperature record was smashed in the northern city of Phalodi in the state of Rajasthan. Temperatures soared to 51℃, beating the previous record set in 1956 by 0.4℃. Also, 2015 saw a flood in a city like Udaipur, which was an unheard-of phenomenon in this region!

India is known for its unbearably hot conditions at this time of year, just before the monsoon starts. Temperatures in the high 30s are normal, with local authorities declaring heatwave conditions only once temperatures reach a stifling 45℃.

Much of India is mostly in the grip of a massive drought. Water resources are scarce across the country. Dry conditions make extreme temperatures worse because the heat energy usually taken up by evaporation heats the air instead.

However, a study found a significant increase in the frequency of extreme temperatures and a remarkable trend in the duration of warm spells in India, as the graph below shows. Warm spells, defined as at least six days of extreme temperatures relative to the location and time of year, increased by at least three days per decade over 1951-2010 – the largest trend recorded globally.

Sky rocketing temperatures across northern and southern India have resulted in the deaths of more than 1,242 people though officials warn that the death toll would be much higher since a larger number of heat-related deaths in rural India go unreported.

Most of these deaths are caused by heatstroke and extreme dehydration. Doctors point out that long exposure to extreme heat raises the body temperature to such a high level that it causes the over-heating of an individual’s protein cells negatively impacting the individual’s brain. Many of those dead are known to be daily labourers, who have no choice but to go out everyday in search of their daily bread.

The searing heat wave in Delhi has seen over 200 dead, the majority of whom were homeless.

Indian Meterological Department presently categorises Rajasthan, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Vidarbha, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Telangana, coastal Andhra Pradesh and north Tamil Nadu as experiencing heat wave conditions annually which extend for eight days and more.

A heat wave condition prevails when the temperature rises to 40 degrees Celsius and more. For hill stations, the heat wave conditions are those where the temperature rises to above 30 degrees Celsius.

Dr D S Pai, a scientist at IMD, warned that severe heat wave conditions are resulting in the death of thousands of people every year. He cites the example of how 1,000 people were killed by a heat wave in Andhra Pradesh in 2002 while another 1,000 people died in the state in 2010.

The causes

Glacial melting and increasing deforestation is also adversely impacting weather cycles and is something that is happening in India too.

The report states that the total amount of carbon human beings emit should not exceed 800 gigatons, but by 2011, 531 gigatons had already been emitted.

The effects of this overdose are for everyone to see — a relentless heating up of the atmosphere with sea levels increasingly flooding coastal plains in India and other countries.

Scientists at the Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, associated closely with the drafting of this report, warn that rising temperatures will adversely impact monsoons. Rainfall is expected to increase by 10 per cent between December to February and up to 50 per cent between September and November and the overall monsoon winds are likely to weaken.

According to the report, Monsoon retreat dates are likely to be delayed, resulting in the lengthening in the monsoon season in many regions.

Higher rainfall will not mean an extension of rainy days. Rather, it will see an increase in extreme weather events as happened during the torrential rainfall that hit Uttarakhand in June 2013 and in 2015 and the heavy rainfall that caused flooding of the Jhelum river in Jammu and Kashmir in 2014 causing destruction in a large part of the capital city of Srinagar.

Apprehensive of the rapid rate of glacial melt, the Nepal-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development said that 54,000 glaciers in the Himalayas could create glacial lakes which would rupture their banks and destroy the surrounding infrastructure and agriculture. The bursting of the glacial lake in Kedarnath precipitated the devastation in Uttarakhand.

A similar lake like this has been created by landslides on the Kali Gandaki river in Nepal after the massive earthquake in Kathmandu in April 2016. If the lake breaches, it would result in disastrous downstream flooding which would spread up to several cities in Bihar.

Scientists question how increasing urbanisation will handle future climate problems, especially since cities produce three quarters of greenhouse gas emissions related to household consumption. The current government’s emphasis on ‘urbanising India’ casts heavy doubts on the future of cities and the environment.

A bad monsoon would mean one more year of poor rains and see a decline in food production.

What can be done?

India is already highly vulnerable to the health impacts of oppressive heatwaves and, as climate change continues, this vulnerability will grow. It is therefore important that heat plans are put in place to protect the population. That’s a difficult prospect in places that lack communications infrastructure or widespread access to air conditioning.

In the longer term, this episode shows that the global warming targets agreed in Paris have to be taken seriously, so that unprecedented heatwaves and their deadly impacts don’t become unmanageable in this part of the world.

(Chaitra runs a website on alternative (eco-friendly) methods of celebrating Ganeshotsav : www.greenbappa.in. She also runs an NGO ‘Rupantar’ working on women empowerment and have previously been selected as one of the 30 fellows to attend the ‘Emerging leaders in Multifaith Climate change movement’ in Rome, 2015.)